Anxiety and excessive worry have become common in today’s fast-paced lifestyle. While occasional stress is normal, constant overthinking, fear, or nervousness can slowly affect your mental, emotional, and physical well-being. Understanding the signs early helps you take control before it becomes overwhelming.

Part 1: The Core Content:-

1. Introduction: The Invisible Weight

We live in an age of anxiety. From the incessant pinging of notifications to global uncertainties, the modern human brain is constantly bombarded with stimuli that trigger our primal survival instincts. But what happens when that survival instinct refuses to turn off?

Anxiety is more than just “feeling stressed.” It is a physiological and psychological state that can debilitate your daily life, turning simple tasks into insurmountable mountains. If you find yourself trapped in a loop of “what ifs” and catastrophic thinking, you are not alone. In this comprehensive guide, we will dismantle the mechanics of anxiety, explore the neuroscience of worry, and provide actionable, evidence-based strategies to reclaim your peace of mind.

2. Defining the Beast: Anxiety vs. Worry

To defeat the enemy, you must first name it. While often used interchangeably, stress, worry, and anxiety are distinct siblings in the family of mental unrest.

- Worry is cognitive. It happens in your mind. It is specific (e.g., “Will I miss my flight?”) and temporary.

- Anxiety is visceral. It happens in your body and mind. It is often diffuse, lingering, and can occur even without a specific trigger.

- Stress is a response to an external threat. Once the threat is resolved, stress usually subsides.

The Clinical Distinction: According to the Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) is diagnosed when excessive worry persists for more than six months and interferes with daily life. It is the difference between feeling nervous before a speech and feeling nervous all the time for no apparent reason.

3. The Neuroscience of “The What Ifs”

Anxiety is not a character flaw; it is biology gone awry.

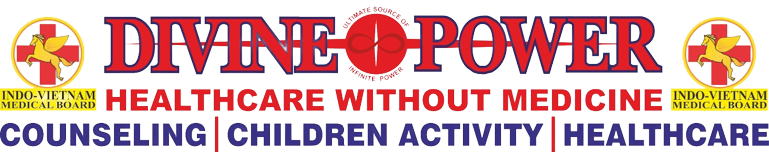

The Amygdala Hijack: Deep in your temporal lobes lies the amygdala, the brain’s “smoke detector.” In anxious individuals, this detector is hypersensitive. It perceives a vague email from a boss as a life-threatening event, identical to spotting a predator in the wild.

The Cortisol Bath: Once triggered, the HPA axis (Hypothalamus-Pituitary-Adrenal) floods your system with cortisol and adrenaline. This prepares you to “fight or flight,” shutting down non-essential functions like digestion and immune response. Chronic anxiety means your body is marinating in these stress hormones 24/7.

Part 2: The “Deep Dives”

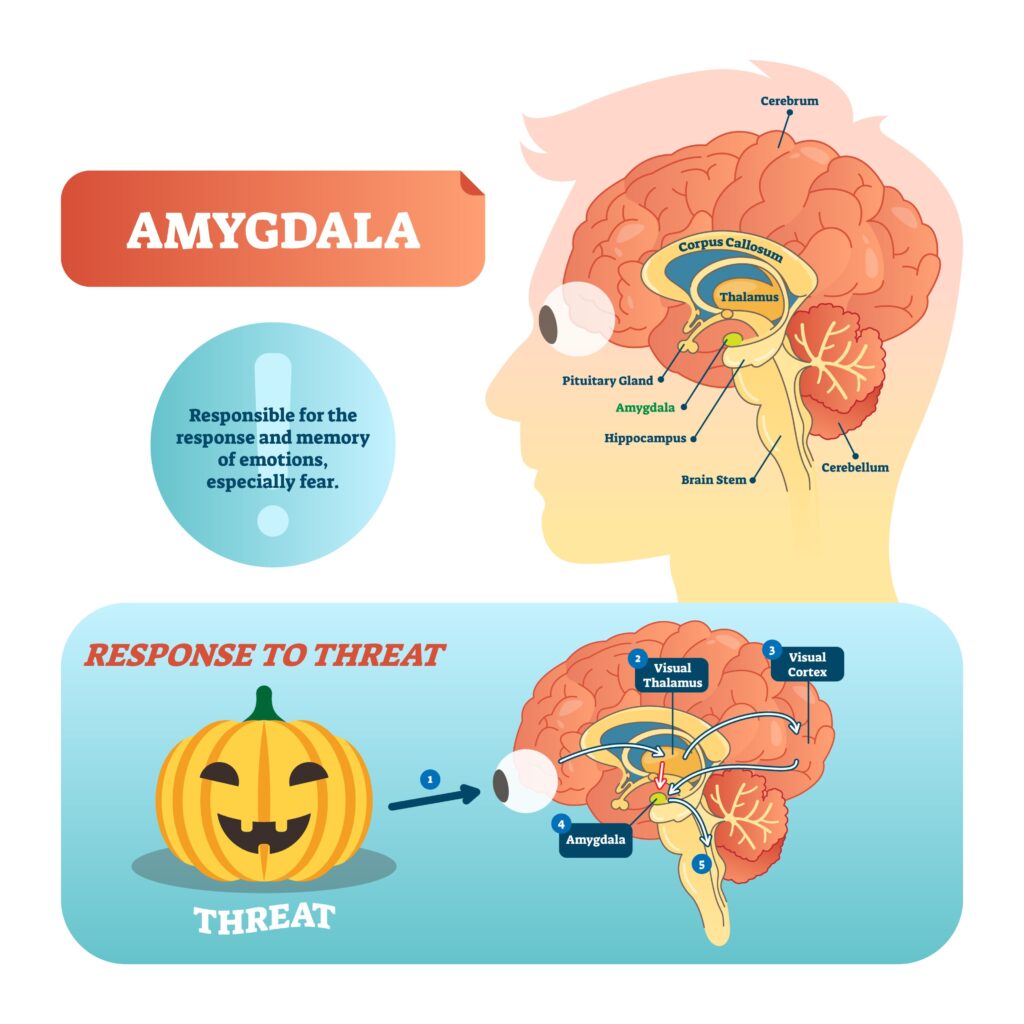

Module A: The Gut-Brain Connection

Key Concept: The “Second Brain” or Enteric Nervous System.

- The Vagus Nerve: Explain how 80-90% of serotonin (the happiness hormone) is actually produced in the gut, not the brain.

- Microbiome: Discuss how an imbalance in gut bacteria (dysbiosis) sends distress signals to the brain, causing anxiety.

- Actionable Content: List “Psychobiotics” (foods like kefir, kimchi, and sauerkraut) that reduce anxiety symptoms.

- A diagram of the bi-directional brain-gut axis, the relationship between the brain and the gut-stomach. The text below the diagram reads “Bidirectional Connection” and is written in a scientific style

Module B: Sleep Architecture & Insomnia

Key Concept: The bidirectional relationship between sleep and worry.

- Sleep Architecture: Explain the difference between REM (where emotional processing happens) and Deep Sleep (physical repair). Anxious people often have “fragmented REM.”

- The “Tired but Wired” Phenomenon: Explain the role of high nighttime cortisol preventing the onset of sleep.

- CBT-I (Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia): Detail this specific treatment, including “sleep restriction” techniques.

Module C: High-Functioning Anxiety in the Workplace

Key Concept: Success on the outside, panic on the inside.

- The “Over-Functioner”: Describe the person who channels anxiety into perfectionism and over-achievement.

- Burnout vs. Anxiety: How to tell the difference.

- Imposter Syndrome: The persistent fear of being exposed as a “fraud” despite evidence of competence.

Module D: Anxiety in Relationships

Key Concept: Attachment Theory.

- Anxious Attachment Style: Explain how childhood inconsistency leads to adult reassurance-seeking.

- The “Pursuer-Distancer” Dynamic: How an anxious person chases a partner, causing the partner to withdraw, which creates more anxiety.

- Co-Regulation: How partners can help soothe each other’s nervous systems without becoming codependent.

Part 3: The Solutions (Actionable Strategies)

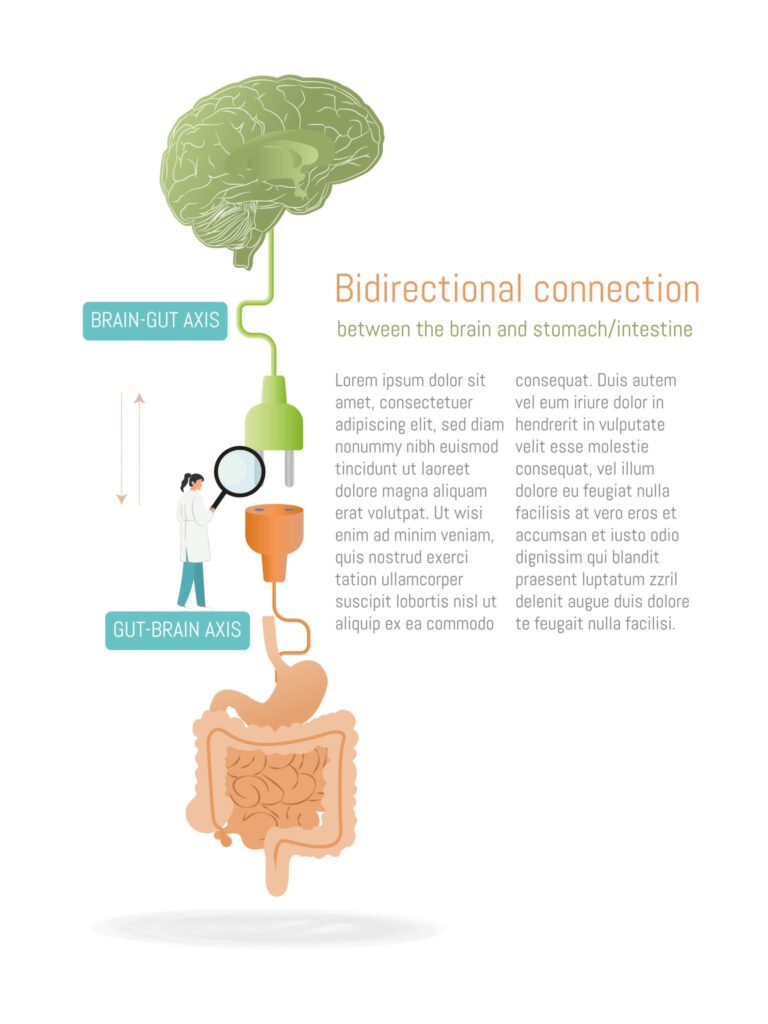

1. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

CBT is the gold standard for treatment. It focuses on the “Cognitive Triangle”: Thoughts, Feelings, and Behaviors.

- Identify Cognitive Distortions:

- Catastrophizing: Assuming the worst possible outcome.

- All-or-Nothing Thinking: “If I fail this test, my life is over.”

- Mental Filtering: Focusing only on the negative details.

- The “Reframing” Technique: Challenge your thoughts. Ask: “Is this thought a fact or an opinion? What evidence do I have?”

2. Somatic (Body-Based) Techniques

You cannot think your way out of a problem you felt your way into.

- The 3-3-3 Rule: Look at 3 things, hear 3 sounds, move 3 body parts. This engages the frontal lobe and dampens the amygdala.

- Box Breathing: Inhale 4s, Hold 4s, Exhale 4s, Hold 4s. This physically forces the parasympathetic nervous system (rest and digest) to activate.

3. Nutritional Psychiatry

- Magnesium: The “nature’s chill pill.”

- Omega-3 Fatty Acids: Critical for brain health and reducing neuro-inflammation.

- Caffeine: Explain why people with GAD should avoid caffeine (it mimics the physical sensation of a panic attack).

Deep Dive: The Neuroscience of Anxiety

(Insert this section after your “Defining the Beast” introduction)

To truly overcome anxiety, we must stop viewing it as a defect of character and start understanding it as a specific set of biological mechanisms. Anxiety is not “all in your head”—or rather, it is in your head, but it is rooted in complex neural circuitry, chemical messengers, and ancient survival instincts.

When you understand the mechanics of the machine, you can learn how to operate the manual override.

1. The Amygdala: Your Internal Smoke Detector

At the heart of the anxiety response sits the amygdala, an almond-shaped structure located deep within the temporal lobes. Neuroscientists often refer to the amygdala as the brain’s “smoke detector.” Its primary job is to scan the environment for threats and initiate a survival response.

In a non-anxious brain, the amygdala works in harmony with the Prefrontal Cortex (PFC). The PFC is the CEO of the brain—it handles logic, reasoning, and impulse control.

The “Low Road” vs. The “High Road” When you encounter a potential stressor—let’s say, a loud noise—your brain processes it in two ways:

- The High Road (Slow & Accurate): The sensory information goes to the thalamus, then to the cortex for analysis (“Is that a gunshot or a car backfiring?”), and finally to the amygdala. The PFC realizes it was just a car, and tells the amygdala to stand down.

- The Low Road (Fast & Dirty): The information goes directly from the thalamus to the amygdala. The amygdala doesn’t wait for confirmation; it hits the panic button immediately.

The Hijack For those suffering from Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD), the connection between the rational PFC and the emotional amygdala is weakened. The amygdala becomes hypersensitive, hitting the panic button for non-life-threatening events—an unanswered text, a weird look from a stranger, or a tight deadline. This is known as an “Amygdala Hijack.”

2. The Neurotransmitter Imbalance

Your brain relies on chemical messengers called neurotransmitters to regulate mood and anxiety. Three key players are often involved in anxiety disorders:

- GABA (Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid): This is your brain’s primary “brake pedal.” GABA inhibits neural activity and promotes calmness. Many people with chronic anxiety have lower levels of GABA, meaning their brain struggles to “power down” after a stressor. This is why Benzodiazepines (like Xanax) work—they artificially boost GABA activity.

- Serotonin: Often called the “happiness hormone,” serotonin regulates mood, sleep, and appetite. Low levels are linked to both depression and anxiety. This is why SSRIs (Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors) are the most common first-line treatment for anxiety.

- Glutamate: The opposite of GABA, Glutamate is the brain’s “gas pedal.” It is an excitatory neurotransmitter responsible for learning and memory. However, in an anxious brain, there is often an excess of glutamate, leading to racing thoughts and restlessness.

3. The HPA Axis and The Cortisol Loop

The amygdala triggers the HPA Axis (Hypothalamus-Pituitary-Adrenal), a complex feedback loop between the brain and the endocrine system.

- The Alarm: The Hypothalamus releases CRH (Corticotropin-Releasing Hormone).

- The Messenger: The Pituitary gland detects CRH and releases ACTH into the bloodstream.

- The Response: The Adrenal glands (sitting on top of your kidneys) pump out Cortisol and Adrenaline.

The Problem with Chronic Cortisol Cortisol is helpful in short bursts; it gives you the energy to run from a tiger. But modern stressors (like debt or worries about the future) are constant, not acute. When cortisol remains elevated for weeks or months, it becomes toxic. It begins to:

- Shrink the Hippocampus (the part of the brain responsible for memory).

- Enlarge the Amygdala (making you even more prone to anxiety).

- Suppress the immune system.